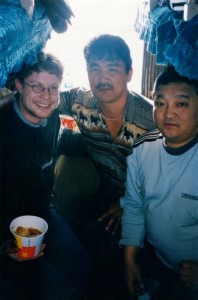

I didn’t know his name at the time, but it was Ardene Baatar. We boarded the train to Mongolia late at night. With our difficult-to-obtain Russian visas and second class train tickets in hand, the conductor showed us to our coupe without a word and left us abruptly to solve the problems of our train life.

I didn’t know his name at the time, but it was Ardene Baatar. We boarded the train to Mongolia late at night. With our difficult-to-obtain Russian visas and second class train tickets in hand, the conductor showed us to our coupe without a word and left us abruptly to solve the problems of our train life.

We took one look at the coupe …just where might we be sitting and sleeping? There was Ardene Baatar sitting on his bed. Every square inch of space our tickets denoted were our beds and the tiny space between were covered with boxes, bags and luggage …Ardene Baatar was everywhere! He and his friend went about moving things an inch or two as if that would solve the problem of sitting and sleeping, but neither Jay nor I would budge. The Mongolian conductor returned finally and made them move almost everything to the baggage car.

Ardene Baatar was not given to hard feelings …a friendly sort from the start, his fellow traveler taciturn and distant. Immediately, a kind of bargaining for information began. Ardene Baatar went first. He lived in Mongolia and was a Mongolian trader. He had just bought clothing from China and was taking it back to Mongolia to sell. Jay and I had the next question to answer …where were we going and was Jay my son. We answered the first question correctly, “To Moscow,” but had I thought to say Jay was my son, I would have avoided trouble later.

The Mongolian train was just filthy. The hallway carpets had rarely, if ever seen a sweeper and the toilets stank. The sheets on the beds were clean, but the blanket grimy…an odor of strong wool, stale bodies and coal dust permeating it‘s roughness. I tried hard not to touch the blanket with my hands as I went to sleep. All night the train bumped and rocked along. Sleepless, I headed for the samovar to make tea many times …it stank of coal fumes. The conductor tried to fix it, but it was a lost cause. In the morning, my hands and face were grimy with soot.

The conductors were steely-eyed and crafty …men who knew how to buy and sell just about anything …and did. They were men who knew exactly how to keep order on a rough train filled with rough and ready men who traveled the world in search of cheap merchandise to sell at home or wherever they could. I drank Chinese tea throughout the night. Ardene Baatar didn’t think much of my tea. He said so. He drank a dark brew made from tiny leaves he stored in a glass bottle …his tea smelled wonderful. Over the next two days, although he offered food at every opportunity, he never offered his tea that he stored in a plastic bottle with a red cap. The bottle was almost empty and had presumably decreased with the miles. Perhaps there was an ancient tea road etched in his brain that reminded him of the value of tea …a feeling of loss as the last tea leaf fell into the cup …an inexorable emptying of the bottle as the journey continued from one station to the next.

I don’t remember exactly how we communicated. I spoke no Mongolian although I had a phrase book. I spoke some Russian with him. He spoke a little Chinese and English. We got along. When Jay and I would eat what we euphemistically called “train noodles,” Ardene would roar with laughter and say, “Verr-y cheap, verr-y good.” When it was time to eat, Ardene pulled out huge slabs of horse meat. Sometimes he drank kumis, the fermented mare’s milk of the steppes, from an old vodka bottle stopped up with a worn cork. He washed everything down with vodka. He drank plum juice straight from the bottle in the morning, but would never touch the plums. He offered everything to us. We politely refused regretfully…almost anything would have been better than the repetition and short-term safety of train noodles.

Ardene Baatar liked my eyes and it wasn’t long before he spilled his precious tea on me and tried to help wipe it off my pants with his hand …except his hand moved to my calf and lingered. I gave him a blistering stare and he cowed in the corner for a while. Jay was lying on the upper bunk writing scores of music in his head that he sometimes worked out with the syncopated beat of a hand on the frame of the bed. I told him, “Jay, my friend, time for you to come downstairs for a visit.”

Ardene Baatar’s next idea was to pass around all of our passports. Ardene Baatar showed me his passport first. He had so many stamps in his passport I couldn’t keep track. Ardene Baatar had traveled the world. He was married and had two children, a boy, age 13, and a girl, age 10. Was he happy to be going home? I couldn’t tell. I think he would have known when he got there. Next it was my turn …and, then, Jay’s. Ardene Baatar was only curious about my age and then handed my passport back with Jay’s that he hadn’t even opened to look at.

We left China and entered Mongolia at night. So much crazy business went on under everyone’s noses. Lots of money changed hands. The conductors were happy men having received much money to deceive the cops in both countries. Ardene Baatar mumbled over and over that the package next to him had “baby clothes.” Um …hmm …how could I forget the drug routes down Four Color Road in Yunnan? I was silent about that box …but I wondered what was really in it. At Erenhot, he and his friend had taken on six huge boxes of chicken parts and several boxes of apples and oranges. They tried to stuff them in the coupe with no luck. Who knows where they were finally stashed and what had been, perhaps, offered in return for the extra space?

On the first morning, I wanted to sleep. It was so cold on the train. We had entered the frozen wasteland of Mongolia and had already seen wild horses and cows covered with woolen coats. It was probably 30 degrees below outside of the train. I had tried to keep the filthy blanket folded in half for warmth and to avoid touching it, but there was Ardene Baatar “assisting” in unfolding the blanket and covering me up. I told him to stop. A gentleman came to the surface, and he did …a trader, he just wanted to see that he had not made a mistake the first time. He leaned back on the pillow and smiled at me until he fell back with his mouth agape and snored for two hours. The train shook.

On our last morning on the train, Ardene Baatar woke me up very early. I mumbled, “Now, what Ardene Baatar?” He motioned for me to come to the window of the train. He pointed across the desert. The sun was coming up and in the distance I could see a lone, dromedary camel crossing the edge of the desert. Ardene Baatar had given me a parting gift. He smiled sweetly. I bowed a little and thanked him.

Ardene Baatar was a man who lived this until then. He was a man who was an unwritten story that is part of a longer story of a thousand years of Mongolian men crossing the deserts and mountains carrying tea and silk. I looked at Ardene Baatar and saw these men, generation after generation, a never-ending journey hither and yon …stories passed from one generation to the next that I would never hear …never understand.

Ardene Baatar showed me a camel. There was this glimpse into a moment of his living …not on the train, but out on into the grasslands …a place he returned to and knew as home …an uncluttered place …a place unbound. I think of Ardene Baatar sometimes. I imagine the camel …a ger, a wife, children and horses in a land so wide that it would be hard to imagine living there less than free.