I saw them on the Moscow-Ulaanbataar-Peking line… four Russian men traveling. They had a feral, train look to them that Jay and I felt we were acquiring ourselves. They seemed hard-bitten. They were always talking and drinking as I would go by their coupe on the way to the toilets. I was curious. Who were they? What brought them here? I wanted to meet them.

I saw them on the Moscow-Ulaanbataar-Peking line… four Russian men traveling. They had a feral, train look to them that Jay and I felt we were acquiring ourselves. They seemed hard-bitten. They were always talking and drinking as I would go by their coupe on the way to the toilets. I was curious. Who were they? What brought them here? I wanted to meet them.

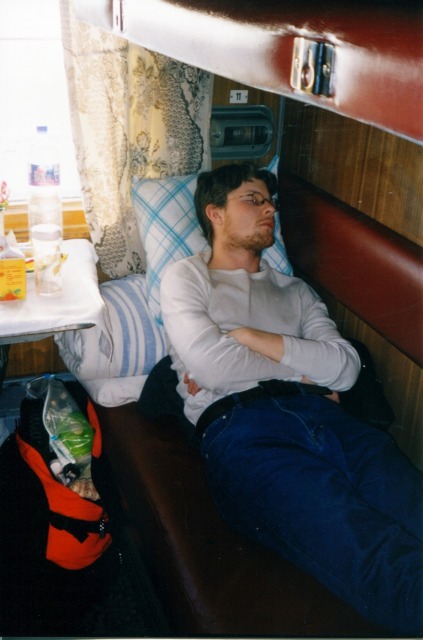

We had boarded late at night in the bitter, damp cold. The Chinese train was completely full and already smelly and dirty. It was a noisy place. Sleep was impossible for the first couple of days until we got used to the clatter… voices in the corridor in the middle of the night… the snapping of the train against the rails in the middle of the night. We would be on this train for a week.

We had a nodding acquaintance with the men when there were stops at the sidings. One or two of them would be outside smoking. They sometimes bought the same things we bought. They would watch us bargain, curious about the price we would pay.

One or both of us were able to get off the train now as we shared our coupe with a placid, Mongolian couple who would watch our things in exchange for watching theirs. We would get off and look at the offerings that we bought from tattered babas in babushkas selling food from baskets. Sometimes we bought boiled eggs or mealy Russian apples long past the time that the juice ran down my chin. Sometimes we were lucky. One time I found Chinese apples, juicy and sweet… once, good oranges… another, excellent blini with cottage cheese handed to me by a bent old woman who took my worn rubles with a gnarled, dirty hand and stuffed them into the cavern of her greasy apron pocket under a lumpy coat. Sometimes we drank orange juice… sometimes vodka. We had run out of the Osmanthus tea of China and drank the dark pekoe from India… Russian tea unfolded from square packages covered in cheap paper… rich with sugar made from the steaming water of the train’s samovar.

We were at the mercy of the train hawkers if we couldn’t find suitable food at the sidings. I shuddered when I heard these words over and over as they trolled the corridors back and forth, “Kapusta… myasa… kartochka. Kapusta… myasa… kartochka.” The” pirozhki” of cabbage, meat or potato stuffed into dough that had been fried in a bubbling cauldron of pig fat this side of rancid weighed us down. The thought of just one more was a death-defying dance with skyrocketing lipids. Ubiquitous train noodles had become part of our lives again. We dreamt and talked of the night we would arrive in Erenhot… the changing of the bogies for the track s’ differing gauge to enter China… a light, hot Chinese dinner of chicken with hot peppers and “tudou si,” the garlicky, julienned potatoes of China, turned out from the wok still crunchy from the ground… spicy with peppers and rich from soy vinegar while we waited to board.

I’d walk by their coupe on the way to the toilet or out onto the siding when we stopped. How to meet them? I wracked my brain. I didn’t want to be forward, but my curiosity was getting the best of me. One day I took a nap. Jay had gone for a smoke. He had met one of them. Jay said that his name was Valery… and then, he had met all of them. He spent a couple of hours with them and was amazed at how much vodka that they had drunk in that space of time… how much they wanted him to drink.

I ran the gauntlet that night to meet Valery with Jay in the greasy dining car. The corridors were thick with drinking, lonely Russian men who didn’t seem to know how to keep their hands to themselves. The train could be fairly settled at night, but a lot of drinking went on and sometimes it was raucous. I was wary and rarely let my guard down.

Valery attempted charm when we met. He said, “Pow-la, y vas kraciviye glaza”… beautiful eyes… and then made some comments about my other body parts. It was clear that he was drunk, but I was determined to carry on with dignity. Soon, he stopped and returned to the “Pow-la, y vas kraciviye glaza” compliment… sincere and sweet.

He bought us vodka and soup, but I insisted on paying for the soup. He poured glass after glass of vodka for me. I drank a little, but it was such swill. When he didn’t look, I am ashamed to admit, I poured it into Jay’s glass. “Sanka” joined us a bit later. I was now sandwiched in between Jay and Sanka on the narrow bench. Sanka was beyond the point of drunkenness and gentlemanly care about where he put his hands. Valery stared him down. The match was short lived. Sanka asked me if I would take him to the United States. I told him I lived in China. He lost interest immediately.

Valery kept up his constant barrage of questions. He insisted that I was a “zhurnalista” who really did know Russian. Finally, he commandeered an officer in the Mongolian army who spoke English and Russian. Now, he could really ask questions. Where was my husband? Where were my mother and father? Why didn’t I have children? Mongolian people are often given to conversational boundaries. The officer didn’t like his role. He apologized at each question more personal than the last.

All evening we drank vodka and glasses of tea on the swaying train… the blue, checked vinyl tablecloths ugly, the florescent light depressing and unreal. Valery would occasionally yell at Sverdlov, a huge Russian who was playing cards in the back of the car. He’d shout, “Sverdlov… mafia,” and laugh. Sverdlov laughed, but his irritation began to show. Then, came the polka music from a tinny tape player. Valery wanted to dance. I said, “Ask Jay, I never dance.”… and Jay told that lie for me, “Paula never dances.” Jay danced with him instead… Jay, my good friend. Valery said he loved Jay like a son. He joked repeatedly, “Jay… O’Henry. Me?… Jack Nicholson… the Classic Man.” Valery did look like Jack Nicholson with his big glasses.

In the morning, I was awakened for breakfast by Valery. He brought me raw bacon, bread and a glass of vodka. My breakfast glared at me. I ignored it. Later, Jay and I went to visit the four men. The two “upstairs” were very quiet,  but Sanka and Valery started the constant chatter and barrage of questions again… and, then, there was another breakfast… a dozen or more peeled, boiled eggs, sausages, bread, more raw bacon, rolls filled with apples, vodka. Finally, I began to piece together the situation of their lives. They all had lived in Moscow. They had no work and were traveling to Mongolia as “construction engineers.” From the look of them, it was hard labor in construction that they really did. Their hands were all rough. Their clothes had seen better days.

but Sanka and Valery started the constant chatter and barrage of questions again… and, then, there was another breakfast… a dozen or more peeled, boiled eggs, sausages, bread, more raw bacon, rolls filled with apples, vodka. Finally, I began to piece together the situation of their lives. They all had lived in Moscow. They had no work and were traveling to Mongolia as “construction engineers.” From the look of them, it was hard labor in construction that they really did. Their hands were all rough. Their clothes had seen better days.

Later in the afternoon, at a stop, Valery breezed by and said, “Pow-la, Pow-la, morozhenoe.” No vodka. Things had changed. I ate the ice cream that he gave me. That night we met Valery in the dining car again. By then, he had begun to tell his friends, “Pow-la, klas.” With this pronouncement that I had class, things had changed and he began to talk.

He had been in the war in Afghanistan and had a very serious shrapnel injury to the knee. He showed me the scar… a palpable testament to the ugliness of war. That knee would never be right again. He said that he had gone to an American hospital. There had been a nurse, Katherine. He talked a lot about Katherine. He said that he still wrote to her. He told me about Katherine as if he was telling a story about a different person, a different life. There was also a wife, Natalya. But, where was Natalya? The threads of his story were tangled. So many things seemed to have gone awry. There was a daughter, but he did not know where she was, just that she was in the United States… and a father in the States, too. Where was his father living in the States? He didn’t know.

We talked about Solzhenitsyn and Yevtushenko. He scoffed and said, “You think that Solzhenitsyn is the only man like that? There are a lot of old men in Russia like Solzhenitsyn..” He loved Yevtushenko. He loved that I had read Yevtushenko. He loved Communism. He wanted to be back in his army days… young, a soldier, proud and strong… and Katherine… always Katherine in the threads of his stories. The night grew long. Jay had drunk too much and I was tired, but we continued talking about O’Henry and Jack London… each a classical love of the Russian people. For a moment, I saw what Valery had been… and was stricken with what he had become. I helped Jay back to the coupe. Valery’s words were in my ears as he repeated down the corridor several times, “Jay… O’Henry… Jay… O’Henry.

After that night, we began to shy away from each other. Our conversation was now spent… the differences in our lives so glaring. I felt such sadness… a powerlessness. We nodded. We spoke. Came the day we reached Ulaanbaatar. The Russians all left unceremoniously with a wave and a “Dosvidanya.”

Those three days visiting with Valery will always seem just like a shooting star to me… a momentary brightness and, then a slow fading and sinking. I wanted to understand why four grizzled men were going from Moscow to Ulaanbaatar. I had wanted to get beyond the barrier of unsolicited flirtation to understand the person who really lived inside Valery. Sometimes, I am unsettled about having done that. I had reminded Valery of a lot of things that he perhaps drank to forget. At night I listened to the train as it hit the uneven rails… a loud snap and after, the expected jolt. I thought of Valery, now many miles away, living his life in Ulaanbaatar.

Those three days visiting with Valery will always seem just like a shooting star to me… a momentary brightness and, then a slow fading and sinking. I wanted to understand why four grizzled men were going from Moscow to Ulaanbaatar. I had wanted to get beyond the barrier of unsolicited flirtation to understand the person who really lived inside Valery. Sometimes, I am unsettled about having done that. I had reminded Valery of a lot of things that he perhaps drank to forget. At night I listened to the train as it hit the uneven rails… a loud snap and after, the expected jolt. I thought of Valery, now many miles away, living his life in Ulaanbaatar.

I thought of him thinking of Katherine. I imagined him reaching for the bottle of vodka.